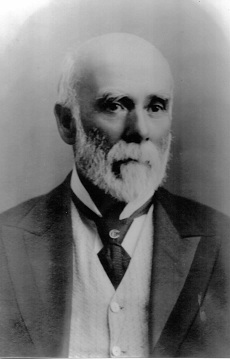

My great grandfather, James Robinson, was born in 1839, the second son of the village blacksmith at Salkeld Gates, Plumpton, north of Penrith on the main road to Carlisle and Scotland. I assume that he attended the village school until he was old enough to be apprenticed to a Mrs Hutchinson who had a grocery business in Market Square in Penrith. He must have learnt the trade well because in 1857 when he was 18 he was sent to Carlisle to manage a shop in Botchergate. Two years later he bought the shop which was at 49 Botchergate, near the present day Border Rambler public house. He was obviously a very ambitious young man and this shop did not satisfy him for long because in 1860, still only 21 years old he bought a derelict property across the road and built a new shop which became known as the Eagle Stores, named after a carved and gilded eagle placed over the door. About this time he began the rural deliveries which became ‘proverbial in the country’ for their regularity and which were a feature of the business throughout its history. The family story is that these deliveries were begun to help country women like his mother who had to walk long distances to and from market with heavy baskets. It is also said that he was the first Carlisle tradesman to employ an errand boy. I do not know if other grocers also did rural deliveries but I think that he may have been a pioneer. In the 1861 census James was listed as a ‘grocer employing two boys’. These were two of his brothers, William and Samuel. He married in 1864 a Scottish farmer’s daughter and they went on to have a family of 5 sons and 2 daughters.

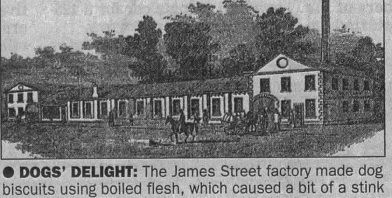

Expansion of the business continued throughout the 1860s with the building of a large warehouse and flour mill behind the shop and extending to Collier’s Lane where there was a second entrance. At this time there was a large factory in James Street just over the railway where a Mr Slater was making biscuits for dogs and humans. The dog biscuits were apparently ‘renowned’ and were mainly exported to Australia during the Gold Rush there but the manufacture from rendered flesh created a ‘poisonous pong’ similar to that created today by Wildriggs which even offended Victorian noses. Mr Slater claimed that the smell was more like a ‘bale of oranges and a rather nice perfume’. For reasons that are unknown this Carlisle Biscuit Company got into financial difficulties and the factory was put up for sale in 1870. James Robinson, extending his business still further bought it for the large sum of £3.750 in 1871.

The selling of groceries and provisions was not James’ only business and in 1877 he was advertising as a miller and bacon curer as well and at some time he also made confectionery and toffee at the James Street factory under the name Eagle Confectionery Company. At the height of this period he was described in the 1881 census as a grocer employing 20 men and 10 boys and his eldest son was an apprentice in the business. One new venture that very nearly caused financial catastrophe however was the manufacture of yeast. At this period apparently most yeast was imported from Germany and James did not think it right that British bakers should have to use foreign yeast so he decided to supply it himself. Unfortunately the manufacturing process produced spirit as a by product and this was very heavily taxed. In the words of James’ grandson, Arthur, writing when he was at school ‘Mr Robinson, however, never lost heart or energy and financed by his father and with his brother Henry Robinson in partnership the grocery business was restarted under the name of James and Henry Robinson, grocers and provision merchants. Henry proved incapable however and retired to start his own business’. The retail branch in Botchergate had been relinquished by this time and sold to the South End Co-operative Society.

Although only one of James’ sons followed him into the business they were all well versed in the trade in their youth. His eldest son who eventually became a Congregational minister wrote in a memoir in a local paper in his old age;-

‘I learnt the grocery, provision and corn trade thoroughly. These were the days when the trade had to be learned. We blended our own tea, learned to buy coffee in the bean, cured much of our own bacon etc. (What a pity he left his list here. I would like to know what ‘etc’ was) ‘The corn trade fascinated me, and I could dress a millstone before I was 17 years old’

James seems to have been interested in the milling process and he applied for several patents for improvements. There was also a Robinson farm on the outskirts of Carlisle so perhaps he grew the corn he milled and the pigs he cured.

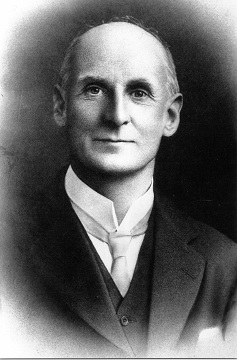

Of James and Barbara’s other sons one became the city veterinary surgeon and his descendents are still vets in Carlisle. James junior however was the one who followed in his father’s footsteps. He was born in 1870 and was eventually taken into partnership in 1903 at the age of 33 having worked in the business all of his life. Also in the same year the James Street premises were sold to Hudson and Scott who were expanding their metal box business and the original shop in Botchergate was demolished.

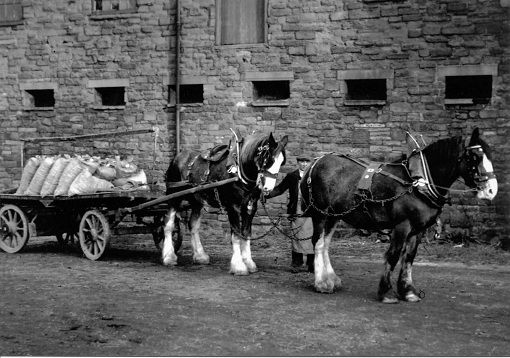

New premises were found in a second old factory, this time a beetling works in Shaddongate near the junction with Caldewgate. Beetling was a process in textile manufacture where cotton cloth was beaten with heavy wooden mallets (beetles) to make it smooth and glossy. This was a large building with plenty of accommodation for the wagons and horses required for the deliveries as well as the retail and wholesale grocery business and it was the home of the Eagle Stores for almost 40 years. James senior died in 1913 at the age of 74. In the obituary in the local paper he was described as;-

Carlisle’s ‘oldest tradesman’ Mr Robinson was a thorough going Free Trader, and believed in social legislation, for few knew as he did the conditions of life in the villages in and around Carlisle.’

James junior was 43 when his father died and had been married for only three years as he had had to help to support his brothers through their training. The business he now controlled was well established with a good reputation for not only the regularity of its delivery journeys but its ‘endeavour to oblige any of (its)customers however small’ in Arthur’s words. At Shaddongate there was not only ample stabling for the Robinson horses and wagons but also for the traps and gigs of customers who came in to market. At some time meals were also provided for them in an upper room before they left on their journeys home. ‘People in the country’ were always very important to the business as the family remembered its rural roots. Arthur wrote of the delivery journeys;-

‘At some period, owing to the difficulty of obtaining carters and goods, the journeys were considerably shortened and reduced in number. In 1914 there were 28 journeys in one month, now (1920s?) there are only 21 and these much shorter than in 1914.’

I guess that the reason for the shortage of carters was the carnage of the First World War.

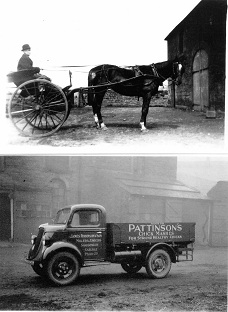

Until the 1930s deliveries would still have been made by horse and wagon but gradually motor vans took over.

James himself never learnt to drive although his wife did and he continued to travel out to get orders in his horse drawn trap. Deliveries were then made in the lorry.

Arthur, my father, James and Dora’s only surviving son, was born in 1911 and he was obviously expected to follow his father into the business. We were told that he would much rather have been something else, a mechanic perhaps, but he accepted his fate and left school at 16 without taking any examinations to start at the bottom of the business and learn the trade. James was apparently stricter with his son than with the other apprentices but Arthur eventually became a Master Grocer in his turn. After working for nine years in the business Arthur, aged 25, was taken into partnership with James in early 1936. The 1930s were, as we know, very difficult years and James must have become depressed about the future of the business because in October of 1936 he committed suicide. The assumption is that he believed that he was about to become bankrupt but there is no proof of this as he left no note of explanation. He must have believed that things were catastrophic though because he was a pillar of the Congregational church and must have thought that suicide was wrong. As is often the way in these things the business was not actually in trouble!

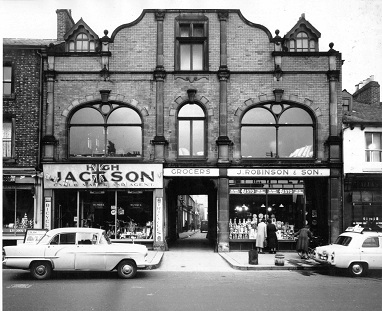

So Arthur was suddenly the sole partner. Two years later he opened a second shop in rented premises at 93 Lowther Street which was in a more central position in the city than Shaddongate and more convenient for the town and local customers. A branch was also opened in Maryport on the west. The start of a chain perhaps! However circumstances changed with the outbreak of WW2 in 1939. Then Dora, Arthur’s mother died in 1940 leaving him free to enlist in the RAF and escape the groceries for a while. A partnership was drawn up with Dick Johnston who had been doing much of the travelling for some years and Henry Banks who managed the financial side of the business giving them authority to run the business in Arthur’s absence. The Shaddongate shop was sold to the city corporation and was run as a British Restaurant before it was finally demolished.

Nobody seems to know what happened to the golden eagle which remained on the building for some time. There was now no need for the stabling that had been provided at Shaddongate as all the deliveries were carried out in motorised transport.

Arthur married Connie Rigg in 1943 and when he was demobbed in 1945 they already had one daughter. On his return to civilian life he once again took over the business which was incorporated as a limited company and renamed James Robinson and Son Limited. He was also involved in teaching grocery apprentices the basics of the trade for the Institute of Grocers and was secretary of the local Grocers’ Association. It was a dreadful shock to everyone when he contracted polio and died in 1948, the day after his 37th birthday.

My mother had absolutely no experience of the business, having been a junior school teacher, and also had two small daughters to bring up single handed so there was no possibility of her taking over. Fortunately Dick Johnston was able to become manager again and he remained at the shop until he retired in 1963. His wife also worked there when their son was old enough. I don’t think that the business impinged much on our consciousness when we were growing up although I do remember playing with some rather attractive black and gold tin boxes which contained small pieces of spices and smelt intriguing – teaching samples I learnt later. We also used a half empty notebook for drawing and writing holiday diaries oblivious to the fact that it contained Arthur’s teaching notes on tea, coffee, tinned fruit, spices and law for budding grocers. I think that the fact that we knew where our grandfather had hanged himself lent a certain frisson to our swinging in the garage. My mother received director’s fees and was involved financially in the business but took no personal part in it until we were both at secondary school in the 1960s and our grandparents, who she had to look after, had both died. In fact during the 1950s many customers thought that it was Johnston’s business rather that Robinson’s! The Maryport branch was wound up in 1956.

When she had more time available Mum decided to volunteer to help assemble and pack orders when there was a shortage of staff. This was a good way of learning about the running of the business which was actually more complicated than she thought. Some merchandise was still bought in bulk and then packed up into smaller amounts for re-sale, taking up a lot of time. Orders had to be checked before dispatch in case mistakes had been made because of interruptions by customers. There were no calculators or electronic tills so sales had to be added up mentally before the total was rung up on the mechanical till. Large ledgers were kept in the office and daily and weekly sales entered in them. I remember that Mum often spent the evenings scanning the new prices in Shaw’s Guide to learn them. She had very well-kept finger nails until she started working in the shop and encountered lots of tins and boxes! Gradually she increased the amount of time she spent working until she was there for a part of every week day apart from Mondays when there were no orders to be made up. She even served behind the counter sometimes when she had mastered the prices and was more confident of finding things. Dick Johnston retired in 1963 and she was nominally the manager although the staff knew more about the business than she did. My sister and I became share holders and I think that I was actually a director as there had to be more than one. According to the minutes of directors’ meetings I attended several of them but as I was at college in London at that time I think that I must have been present in spirit rather than body and I don’t remember going to any.

The 1960s saw the rise of the supermarket and by 1965 it was obvious that the business could not compete and it was losing money. Country people no longer relied on monthly orders as more of them had their own transport and could shop when they wanted to at the supermarket. The premises themselves needed considerable modernisation as new regulations were brought in regarding storage facilities for food, refrigeration etc and there was not enough money coming in to finance this. It was also a very labour intensive business with a large weekly wage bill. There did not seem to be any alternative and the business was brought to an end after just over one hundred years and three generations.

One good result of the shop closure was that Mum got to know the recently widowed accountant well and they were married in 1967.

As it turned out the building itself did survive for many years as it was demolished when The Lanes shopping complex was built in the 1970s. The name Globe Lane is still used for one of the main entrances to The Lanes Shopping Centre.

The layout of the shop as I remember it – with corrections by my mother:

There was a long wooden counter in an inverted L shape along the left hand side and at the far end of the large shop with a bank of small drawers on the wall behind. Under the counter were shelves and containers for goods. At the end near the large front window stood a tall semi-cylindrical japanned tea container. A small side window overlooking Globe Lane had glass shelves for the display of bottles of sweets. Behind the shorter arm of the counter was an alcove with a marble shelf where butter, margarine, lard and cheese were kept. There was also a small refrigerator for the bacon and a hand basin. The bacon slicing machine stood at the end of the counter beside a marble slab for slicing and wrapping on. Down the right hand wall were biscuit tins with glass lift-up lids and tinned goods on shelves. Chairs were provided where customers could sit while their orders were collected. Definitely hands-off shopping for customers but hard work for shop assistants!

A short passage at the side led to the office and the back room where orders were assembled, materials weighed and packaged, bacon rolled and hung etc. The office had a long desk with a sloping top along the wall and tall low backed stools to sit on. Very Dickensian! Photographs of the three generations of Robinsons were hung on the wall and were referred to as the Father, Son and Holy Ghost by the staff. There was a large safe in the corner and bars on the window. Bills were stuck on a spike.

Upstairs on the first floor the large bags of flour, sugar and animal feed were stored. They were loaded onto the vans below in the lane through a door at floor level using a hoist. When the hoist was in operation it also powered a coffee grinding machine. I remember sitting in the large window in this room to watch a procession when Princess Margaret visited Carlisle. The cellar below the shop was used to store cases of tins and bottles which were sent down an ingenious chute which could be lowered over the stairs and then pushed up again when no longer required.